INSIGHTS

Explore our library of resources, reports, tools, and more from IBTS' team of industry experts.

Featured Insight

Central, Louisiana, January 27, 2025 —The City of Central has achieved a Class 5 rating from the National Flood Insurance Program’s Community Rating System, enabling homeowners and businesses to receive a 25% reduction in their flood insurance premiums while enhancing community safety and strengthening property protections. The Community Rating System (CRS) is a voluntary incentive program that recognizes and encourages community floodplain management practices that exceed National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) minimum requirements. More than 1,500 U.S. communities participate in the CRS program by implementing local mitigation, floodplain management, and educational outreach activities. The City of Central is part of the Baton Rouge metropolitan area and has a population of around 30,000. Since 2011, the Institute for Building Technology and Safety (IBTS) has provided municipal services for the City, including leading efforts to improve its CRS rating. “This recognition reflects our ongoing efforts to prioritize public safety and strengthen flood resilience in our community,” said Central Mayor Wade Evans. “We are committed to preserving lives, safeguarding property, and ensuring a secure future for Central’s residents.” Situated between the Comite and Amite rivers, about 60 percent of Central’s incorporated area is within a Special Flood Hazard Area (SFHA); these areas require special NFIP floodplain management regulations and mandatory flood insurance due to their high risk of flooding. In 2016, a catastrophic storm, the fourth most costly flood event in U.S. history at the time, sent multiple rivers to record levels in the state; the Amite exceeded its previous record by more than six feet. Following the flood, the City accelerated its disaster planning and floodplain management efforts, which led to achieving a Class 7 rating in 2020; property owners then received a 15% insurance premium discount due to improved zoning requirements and increased educational programs. Mayor Evans’ commitment to public safety and IBTS’ floodplain expertise continue to drive City planning. Central has undertaken numerous infrastructure projects to counter escalating flood risks, which affect much of Louisiana’s low-lying geography. The City has collaborated with East Baton Rouge Parish on a multi-jurisdictional hazard mitigation plan, implemented an effective hydraulic model to monitor flood and stormwater, and strengthened City ordinances pertaining to building elevation and new development drainage requirements. Future plans include using real-time forecasting models to better prepare for weather events and developing a multi-jurisdictional assessment of floodplain species and plants. Achieving a Class 5 rating “is the result of collaborative efforts to implement effective flood mitigation strategies,” said Brandon Whitehead, Central’s CRS Coordinator. “We appreciate the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the NFIP for their partnership as we continue working toward a safer and more resilient Central.” The new CRS rating, effective October 1, 2025, will automatically renew annually as long as the City complies with NFIP guidelines and continues its certified floodplain management activities. For more information on the City of Central’s floodplain management activities or the NFIP CRS program, contact Karen Johnson, IBTS Market Engagement Program Director, at kjohnson@ibts.org . ### IBTS is a national nonprofit organization and trusted advisor and partner to local, state, and federal governments. Our nonprofit mission to serve and strengthen communities is advanced through our services. These include building code services and regulatory expertise; compliance and monitoring; community planning; disaster planning, mitigation, and recovery expertise; energy solutions; municipal services; grants management; program management and oversight; resilience services; solar quality management; and workforce development and training. IBTS’ work is guided by a Board of Directors with representatives from the Council of State Governments (CSG), the International City/County Management Association (ICMA), the National Association of Counties (NACo), the National Governors Association, and the National League of Cities (NLC).

Latest Insights

News

Podcasts

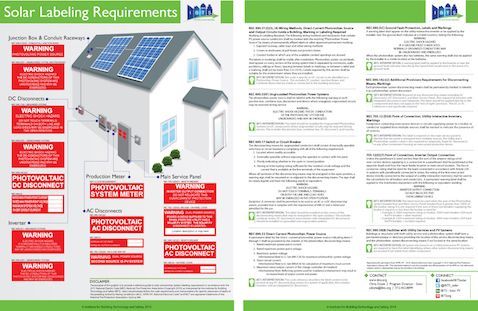

Solar standards are critical to ensuring the performance, resilience, and safety of solar photovoltaic installations and, accordingly, to protecting building owners, installers, manufacturers, and jurisdictions. In this episode of On Further Inspection, learn about the history of solar standards and IBTS' role in their evolution from our guest, Rudy Saporite, Program Director for IBTS' Energy Services.

In this first episode of IBTS' podcast On Further Inspection, host Gabby Geraci invites guests Chris Miller, IBTS Director of Local Government Services, and IBTS Inspector Jesse Harris to share insight into how jurisdictions can benefit from third-party inspections and other building department services.

Case Studies

The Institute for Building Technology and Safety (IBTS) is a national, nonprofit professional services organization providing on-call, third-party building department support for local governments. In this white paper, IBTS shares its experiences with remote building inspections to help jurisdictions evaluate the utility of this emerging approach for their own building departments. IBTS is also seeking to establish a steering committee to help define best practices for local governments. For more information, visit ibts.org/remote

Reach Out

Please use the following contact form to reach out to us with your inquiries and feedback.